Leo Brenner and the Canals of Mars

As anyone who follows this website knows (and I am not sure if anyone does) I don’t have a lot of stamps or a lot of money to spend on them.

But items have more to offer than simply value. It isn’t about how much a stamp is worth. It is about the history and stories behind the stamps or items. The value comes from how much you choose to gain from it. That applies to everything in life, doesn’t it?

Which brings me to this item I recently picked up.

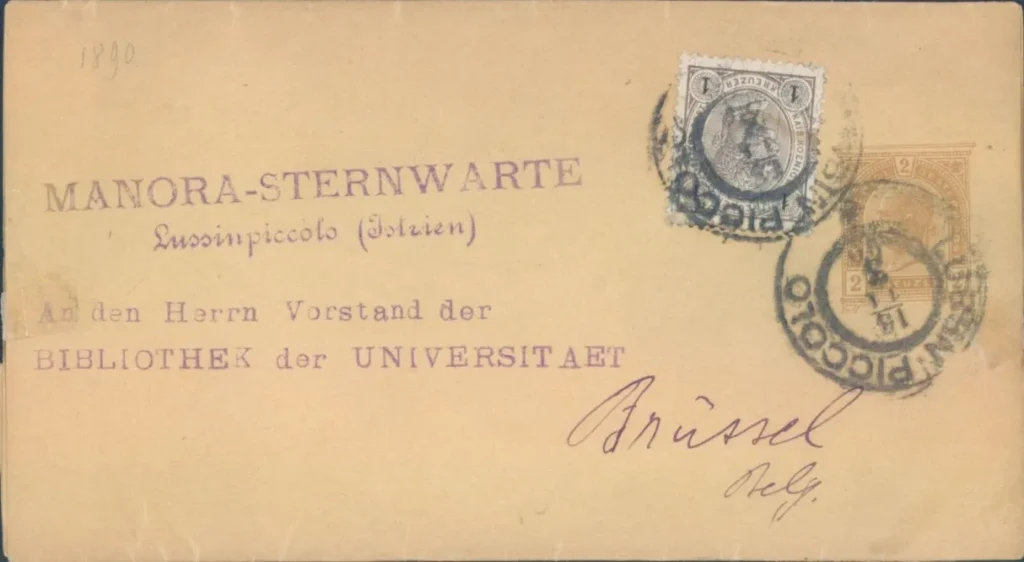

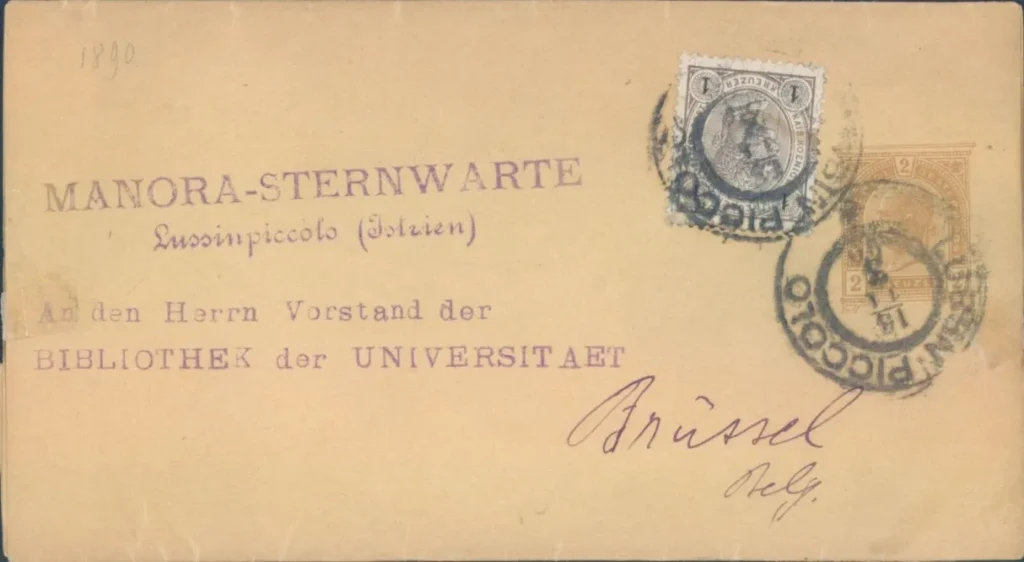

This appears to be a “wrapper”. Usually a wrapper is used to ship a newspaper or periodical. It usually comes with a pre-printed stamp. This wrapper includes the following information:

From:

Manora-Sternwarte

Lussinpiccolo (Istrien)

To:

An den Harrn Varstand der Bibliothek der Universitaet

Brussel, Belg.

The seller had written the date (I assume from the cancellation) as 1890 and the 1kr stamp was issued in 1890. The date on the 2 postmarks are hard to read but I think the actual date is later.

After a deep dive, here is what I think it actually is:

Spiridion Gopčević was born in Trieste (Italy) on July 9th 1855. His father Spiridion was a wealthy ship owner in Trieste and their home was situated in the central part of Trieste called Grand Canal (Canal Grande). When Spiridion was just six years old his father committed suicide because of an economical breakdown, and his mother sent him to Vienna to continiue his studies. After his mother’s death, he left University and started a very successful but controversial career as a journalist. At one point he ends up jailed because of his anti-government writings.

Gopčević marries into a rich Austrian noble family and succeeds in getting funds from the Austrian Government for his next venture. He and his wife settle in Lussinpiccolo (now Mali Lošinj, Croatia) on September 18th 1893. and starts building his Observatory “Manora” (named after his wife). For some unknown reason Gopčević takes his “astronomy name” Leo Brenner and starts his career as an astronomer.

Outfitted with a small refractor telescope with a 3 1/4-inch lens. Fascinated by the wonders of the starry sky, Brenner, over the next five years would spend nearly 3,000 hours at the eyepiece and make nearly 2,000 drawings.

Some of his observations have been applauded. Most have not.

In 1975 Larry Krumenaker of New York University analyzed 21 of Brenner’s Mercury drawings, concluding that at least some of the features he recorded correspond to those shown in Mariner 10 imagery. One striking characteristic in Brenner’s Mercury drawings is the depiction of bright polar caps.

These observations are supported by more recent ones by the French astronomer Audouin Dollfus, who defocused images of Mercury taken by Mariner 10 in the early 1970s – to simulate ground-based telescopic views – and discovered that the planet’s heavily cratered polar regions would indeed appear bright visually.

Brenner thought he saw oceans through holes in the Venus’s dense cloud cover. His drawings show dark features aligned symmetrically about the planet’s equator, resembling the C-, X-, and Y-shaped cloud formations recorded in ultraviolet light by the Pioneer Venus orbiter in 1979. The bright polar caps in Brenner’s drawings have also been confirmed by the spacecraft’s imaging, though they are clouds, not snow as he believed.

Brenner often saw the prolonged horns of Venus when the planet was at quarter phase or more. This strange phenomenon was also seen in 1986 by German amateurs. They thought they had found something new until they learned of Brenner’s observations nearly 100 years earlier.

Brenner believed that Martian canals could have been the work of a past civilization. His map of the red planet shows a maze of canals, 72 of which were discovered at Manora Observatory.

by late 1894 Gopcevic was publishing papers on his observations of the Moon, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn and he became known in the world of astronomy. His articles and observations were published in the best astronomy journals at the time, and he corresponded with the greatest astronomers of that time. Attempting to maintain his reputation, he began to boost his observations with extravagant claims concerning his Mars observations that could not be proved. With that, his reputation began to slide and his articles would no longer be published.

In 1899 he began to publish his own journal called “Astronomische Rundschau” (Astronomical Overview) which ran until 1909. During the eleven years of the journal’s existence, “he filled it with his astronomical essays, his incessant and vituperative polemics, papers by other astronomers”, and he assumed professional titles that were untrue. In its final March 1909 issue, Brenner revealed to his readers that he was a Count (which apparently he was not) and that he had decided to forsake astronomy.

Having lost his reputation as an astronomer, he left behind the field of astronomy, his wife and the city of Lussinpiccolo in 1909 and moved to San Francisco, California, U.S.A. where he wrote music. In 1912, he wrote the lyrics for two operas, “The Paris September Days” and “The Life Saver”. His musical endeavors had little success, so he returned to writing on political themes.

Just before the start of World War I, Gopcevic returned to Europe and worked as editor on an army journal in Berlin where he wrote pamphlets on the theme of the reunification of all South-Slav nationalities under the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. He wrote his last paper in 1922 on the subject of Atlantis and Lemuria. The date most frequently shown as his date of death is 1928, but there are two other dates also mentioned. One of them comes with the claim that “he fell into anonymity and died in Berlin in 1936”.

I believe this is one of the wrappers used to send Astronomische Rundschau out to the University library in Brussels, Belgium and the date is probably not 1890 but 1899. The imprinted postage was not enough so a 1 kr. SC#51 (issued in 1890) was also affixed but since Astronomische Rundschau ran from 1899 to 1909 (103 issues) it could not be postmarked earlier than that so probably 1899.

Update: Since writing this I found a number of scans of wrappers housed in a museum in Croatia.

Today he has relatively unknown but there is a crater on the moon named Brenner in his honor.